Archaeologists in Ecuador have made a fascinating, if rather grisly, discovery. In a burial mound dating back 2,100 years, the scientists found signs of a ritual that has never been seen before – two babies were buried wearing “helmets” made of the skulls of other children.

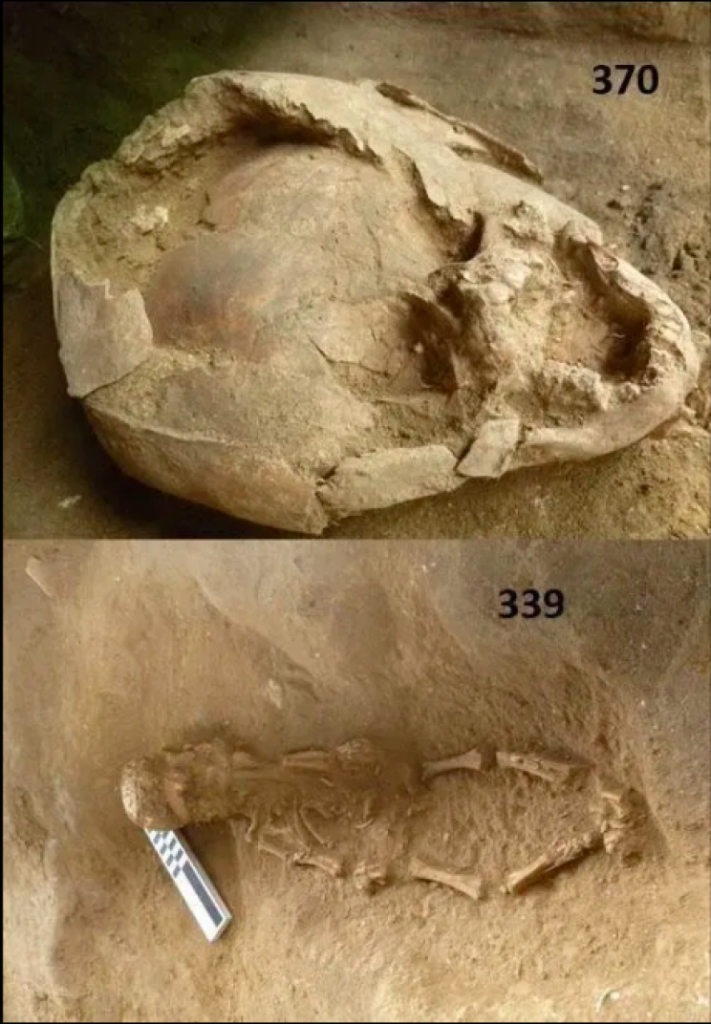

During excavations between 2014 and 2016 in Salango, Ecuador, the remains of eight infants, one child and two adults, were discovered in two small burial mounds. Small artifacts, shells and stone figurines were found around some of them, in keeping with practices seen in other mounds. But two of the infants stood out as peculiar – their skulls were wrapped in larger skulls, in an apparent burial ritual that’s never been seen anywhere else in the world.

The first baby was estimated to have been about 18 months old at time of death. According to the researchers the skull of an older child, aged between four and 12 years old, had been fitted over the infant’s head like a helmet, “such that the primary individual’s face looked through and out of the cranial vault of the second.”

There wasn’t much space between the two skulls, so the team believes that the helmet was placed at the time of burial. A small shell and part of a child’s finger bone were also found between the two skull layers. The second infant was estimated to have been between six and nine months old, and the original owner of its skull helmet was believed to have been between two and 12 years old.

“The skulls were fairly well preserved, although fragmentary from normal erosional processes associated with being buried,” Sara Jeungst, corresponding author of the study, tells New Atlas. “The outer skulls had straight edges, suggesting they had been cut, although only one cut mark was found.”

But there’s an even grislier twist. The position of some bones of the outer skulls suggested that the helmets were “processed” and likely even fitted over the infants’ heads while they were still covered in flesh.

So why would people in the year 100 BCE bury their children like this? In the context of ancient South American cultures, the researchers say that the human head was a strong symbol of identity.

“Heads were commonly depicted in iconography, pottery, stone, and with literal heads in pre-Columbian South America,” Jeungst tells us. “They are generally representative of power, ancestors, and may demonstrate dominance over other groups – such as through the creation of trophy heads from conquered enemies.”

In this case, the extra skulls may have been an attempt to protect the young souls. Stone figurines of ancestors, which had been placed around the heads of other infants buried there, adds evidence to support this idea.

The team says there are other clues to the story in and around the burial mound. While child sacrifices are common to ancient cultures in the area, there was no forensic evidence that these children had been sacrificed. They did, however, show signs of severe disease or malnourishment prior to death, which may have been the result of volcanic eruptions.

“These burials are buried just above a layer of volcanic ash, likely associated with an eruption in the highlands, so we suggest that there may have been resource stress post-eruption (loss of crops, or trouble finding regular marine foods) which could have triggered disease outbreaks, and thus the ritual interment of these children with extra ‘protection’ or enhanced connection with ancestral figures,” Jeungst tells us.

The researchers hope to conduct DNA studies to determine whether the infants were related to the children whose skulls they were wearing.

The bones were originally excavated by Richard Lunniss, and the dig was funded by the Universidad Tecnica de Manabi.